This blog post is written by AI CDT student, Isabella Degen

A summary of Prof. Kerstin Eder’s talk on the well-established procedures and practices of verification and validation (V&V) and how they relate to AI algorithms. The objective is to inspire the readers to apply better V&V processes to their AI research.

Verification is the process used to gain confidence in the correctness of a system compared to its requirements and specifications. Validation is the process used to assess if the system behaves as intended in its target environment. A system can verify well, meaning it does what it was specified to do, and not validate well, meaning it does not behave as intended.

V&V are challenging for systems that fully or partially involve AI algorithms despite V&V being a well-established and formalised practice. Many AI algorithms are black boxes that offer no transparency about how the algorithm operates. They respond with multiple correct answers to similar or even the same input. AI algorithms are not deterministic by design. Ideally, they can handle new situations well without needing to be trained for all situations. Therefore, accurately and exhaustively listing all the requirements against which these algorithms need to be verified is practically impossible.

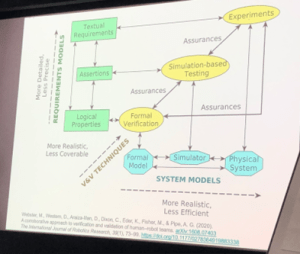

V&V methods for complex robotic systems like automated vehicles are well-established. Automated vehicles need to be capable of operating in an environment where unexpected situations occur. Various ISO standards (ISO 13485 – Medical Devices Quality Management, ISO 10218-1 – Robots and Robotic Devices, ISO 12207 – Systems and Software Engineering) describe different V&V practices required for software, systems and devices. These standards expect the use of multiple processes and practices to meet the required quality. No one practice covers the extent of V&V each practice has shortcomings. The three techniques for V&V are formal verification, simulation-based verification and experiments [3]. The image below arranges these techniques by how realistic and coverable they are, where coverability refers to how much of the system a technique can analyse [1].

The image shows the framework for corroborative V&V [1].

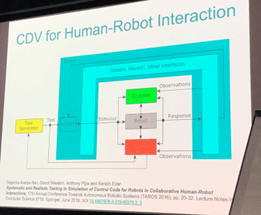

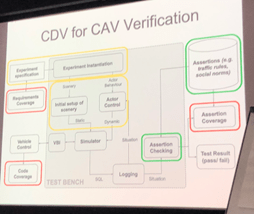

An approach for simulation-based testing is coverage-driven verification (CDV). A two-tiered test generation approach where abstract test sequences are computed first and then concretised has been shown to achieve a high level of automation [2]. It is important to note that coverage includes code coverage, structural coverage (e.g. employing Finite State Machines) and functional coverage (including requirements and situations).

The images show the CDV process (left) and its translation to an automated vehicle scenario (right) [2].

Belief-desire-intention (BDI) agents used as models can further generate tests. These agents achieve coverage that is higher or equivalent to model-checking automata. The BDI agents can emulate the agency present in Human-Robot Interactions. However, the cost of learning a belief set has to be considered [3]. Similarly, software testing agents can be used to generate tests for simulation-based automated vehicle verification. Such an agency-directed approach is robust and efficient. It generates twice as many effective tests compared to pseudo-random test generation. Moreover, these agents are encoded to behave naturally without compromising the effectiveness of test generation [4].

The hope is that inspired by these techniques used to test robotic systems we will promote V&V to first-class citizens when designing and implementing AI algorithms. V&V for AI algorithms requires innovation and a creative combination of existing techniques like intelligent agency-based test generation. The reward will be to increase trust in AI algorithms.

References:

[1] Webster, Matt, et al. “A corroborative approach to verification and validation of human–robot teams.” The International Journal of Robotics Research 39.1 (2020): 73-99. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0278364919883338

[2] Araiza-Illan, Dejanira, et al. “Systematic and realistic testing in simulation of control code for robots in collaborative human-robot interactions.” Towards Autonomous Robotic Systems: 17th Annual Conference, TAROS 2016, Sheffield, UK, June 26–July 1, 2016, Proceedings 17. Springer International Publishing, 2016. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-40379-3_3

[3] Araiza-Illan, Dejanira, Anthony G. Pipe, and Kerstin Eder. “Model-based test generation for robotic software: Automata versus belief-desire-intention agents.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.08439 (2016). https://arxiv.org/abs/1609.08439

[4] Chance, Greg, et al. “An agency-directed approach to test generation for simulation-based autonomous vehicle verification.” 2020 IEEE International Conference On Artificial Intelligence Testing (AITest). IEEE, 2020. https://arxiv.org/abs/1912.05434

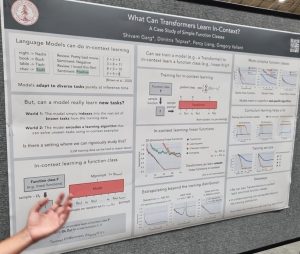

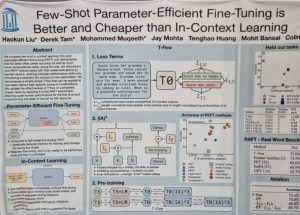

tasks without updating their weights from examples given in the model’s input prompt. Models like GPT3 can perform in-context learning from small numbers of examples. Garg et al. presented an interesting paper that triez to understand what classes of functions can be learned in this way [1]. They were able to train Transformers that learn function classes including linear functions and two-layer neural networks.

tasks without updating their weights from examples given in the model’s input prompt. Models like GPT3 can perform in-context learning from small numbers of examples. Garg et al. presented an interesting paper that triez to understand what classes of functions can be learned in this way [1]. They were able to train Transformers that learn function classes including linear functions and two-layer neural networks.

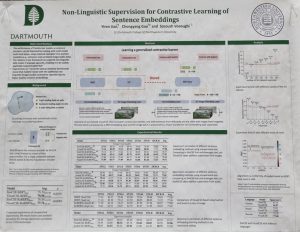

Vosoughi [3] learns sentence embeddings usingimage and audio data alongside a text training set. The method works by creating pairs of images (or audio) using data augmentation, which are then embedded and fed through a BERT-like transformer to provide additional data for contrastive learning. This is especially useful for low-resource languages and domains, and it is really interesting that we can learn from different modalities without any parallel examples.

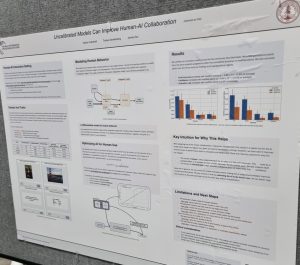

Vosoughi [3] learns sentence embeddings usingimage and audio data alongside a text training set. The method works by creating pairs of images (or audio) using data augmentation, which are then embedded and fed through a BERT-like transformer to provide additional data for contrastive learning. This is especially useful for low-resource languages and domains, and it is really interesting that we can learn from different modalities without any parallel examples. Many machine learning researchers are concerned with models that produce well-calibrated probabilities, but what difference does calibration make to end users? Vodrahalli, Gerstenberg and Zou [4] investigated a binary prediction task in which a classifier provides advice ta user, along with its confidence. They found that exaggerating the model’s confidence led the user to perform better. So, the classifier was uncalibrated and had higher training loss but the complete human-AI system was more effective, which shows how important it is for ML researchers to consider real-world use cases for their models.

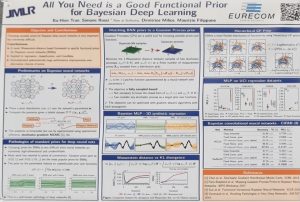

Many machine learning researchers are concerned with models that produce well-calibrated probabilities, but what difference does calibration make to end users? Vodrahalli, Gerstenberg and Zou [4] investigated a binary prediction task in which a classifier provides advice ta user, along with its confidence. They found that exaggerating the model’s confidence led the user to perform better. So, the classifier was uncalibrated and had higher training loss but the complete human-AI system was more effective, which shows how important it is for ML researchers to consider real-world use cases for their models. deep learning aims to quantify uncertainty in complex neural network models, but is challenging to apply as it is difficult to specify a suitable prior distribution. Ideally, we’d specify a prior over the functions that the network encodes, rather than over individual network weights. Tran et al. [4] introduce a method for setting functional priors in Bayesian neural networks, by aligning them with Gaussian processes. It will be interesting to try out their approach in some deep learning applications where quantifying uncertainty is important.

deep learning aims to quantify uncertainty in complex neural network models, but is challenging to apply as it is difficult to specify a suitable prior distribution. Ideally, we’d specify a prior over the functions that the network encodes, rather than over individual network weights. Tran et al. [4] introduce a method for setting functional priors in Bayesian neural networks, by aligning them with Gaussian processes. It will be interesting to try out their approach in some deep learning applications where quantifying uncertainty is important. few-shot generalization and personalization, which learns from semantic descriptions of classes, providing a way for instruct models through text.

few-shot generalization and personalization, which learns from semantic descriptions of classes, providing a way for instruct models through text.  and constraints. She emphasized that the way people refer to desired actions provides important information about their preferences, and therefore we can infer, from a user’s language, reward functions that reflect their preferences. Aida Nematzadeh compared self-supervised pretraining to language learning in childhood, which involves interacting with other people. Her talk focused on the evaluation of neural representations, and she called for real-world evaluations, strong baselines and probing to provide a much more thorough way of uncovering the strengths and weaknesses of pretrained models.

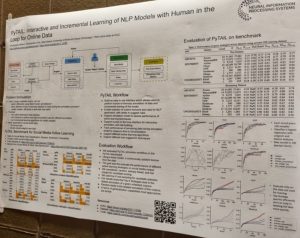

and constraints. She emphasized that the way people refer to desired actions provides important information about their preferences, and therefore we can infer, from a user’s language, reward functions that reflect their preferences. Aida Nematzadeh compared self-supervised pretraining to language learning in childhood, which involves interacting with other people. Her talk focused on the evaluation of neural representations, and she called for real-world evaluations, strong baselines and probing to provide a much more thorough way of uncovering the strengths and weaknesses of pretrained models. techniques to software libraries and benchmark datasets. For example, PyTAIL [2] is a Python library for active learning that collects new labelling rules and customizes lexicons as well as collecting labels. Mohanty et al. [3] developed the IGLU challenge, in which an agent has to perform tasks by following natural language instructions; their presentation at InterNLP explained how they collected the data. The RL4M library [4] provides a way to optimize language generation models using reinforcement learning, as a way to adapt to human preferences; the paper [4] also presents a benchmark, GRUE, for evaluating RL methods for language generation. Majumder and McAuley [5] investigate the use of explanations to debias NLP models while maintaining a good trade-off between predictive performance and bias mitigation.

techniques to software libraries and benchmark datasets. For example, PyTAIL [2] is a Python library for active learning that collects new labelling rules and customizes lexicons as well as collecting labels. Mohanty et al. [3] developed the IGLU challenge, in which an agent has to perform tasks by following natural language instructions; their presentation at InterNLP explained how they collected the data. The RL4M library [4] provides a way to optimize language generation models using reinforcement learning, as a way to adapt to human preferences; the paper [4] also presents a benchmark, GRUE, for evaluating RL methods for language generation. Majumder and McAuley [5] investigate the use of explanations to debias NLP models while maintaining a good trade-off between predictive performance and bias mitigation.

discussion – thanks to John Langford, Karthik Narasimhan, Aida Nematzadeh, and Alane Suhr for taking part, and thanks to the audience for some great interactions too. The wide-ranging discussion touched on the evaluation of interactive systems (how to use static data for evaluation, evaluating how well models adapt to user input), working with researchers and users from other fields, different forms of interaction besides language, and challenges that are specific to interactive NLP.

discussion – thanks to John Langford, Karthik Narasimhan, Aida Nematzadeh, and Alane Suhr for taking part, and thanks to the audience for some great interactions too. The wide-ranging discussion touched on the evaluation of interactive systems (how to use static data for evaluation, evaluating how well models adapt to user input), working with researchers and users from other fields, different forms of interaction besides language, and challenges that are specific to interactive NLP.